The Wild Problem (above): would you like to be turned into a vampire?

Wild Questions (above):Would you like to be turned into a vampire?

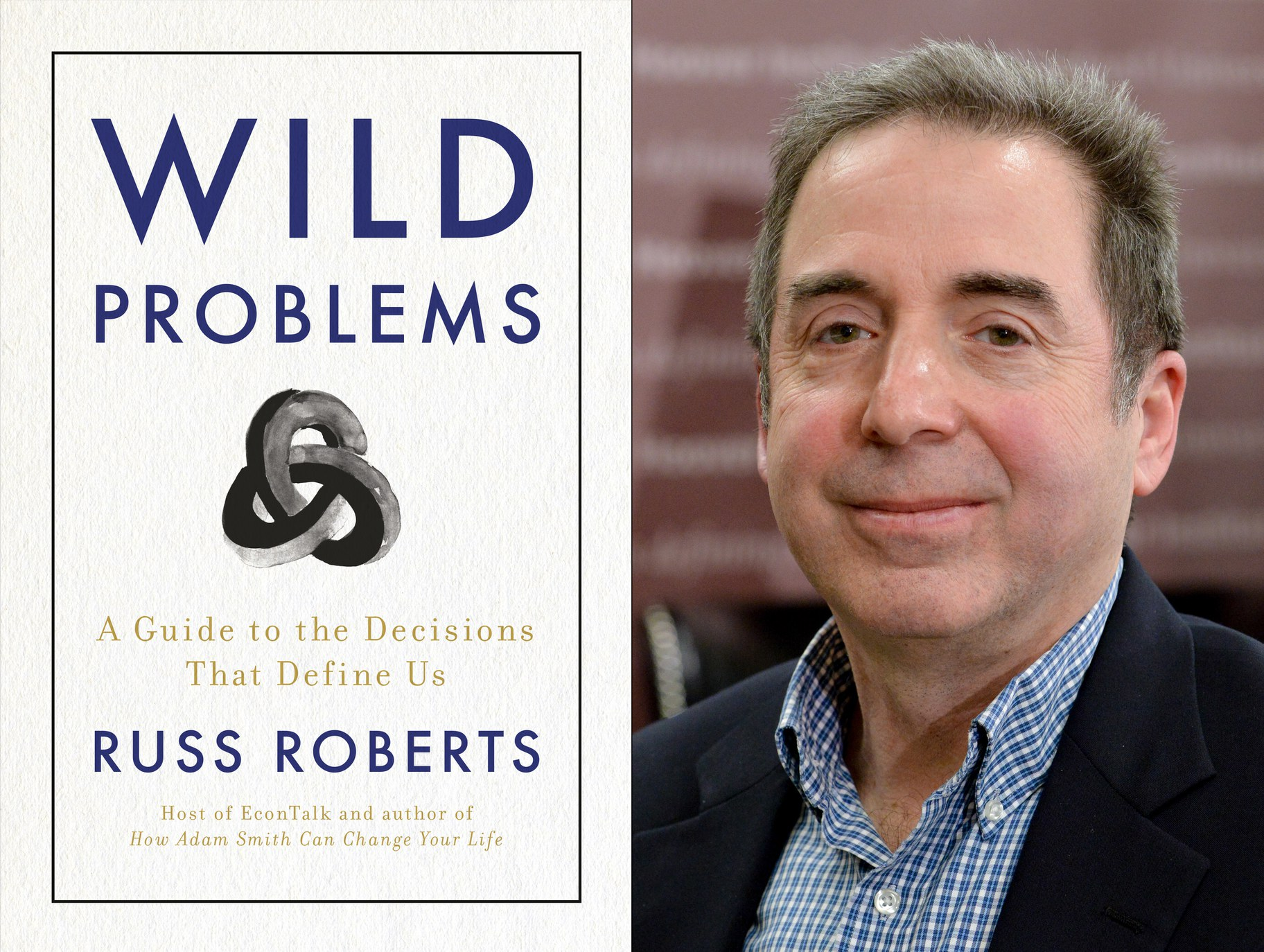

We start today with a new book that comes out August 9, 2022, Wild Problems: A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us in Life. The author of the book, Russ Roberts, who is a fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and recently hired as the president of Shalem College in Jerusalem, Israel, also has a podcast called EconTalk, which I listen to a little bit sometimes.

Our column has talked before about a book Roberts published in 2014, How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life [1].

Roberts was originally in economics, and Shalom College specializes in the humanities, a place dedicated to training Israel’s future leaders. We can also see from this book that Roberts shifted from economics to the humanities.

There are truths in this book that you may not necessarily use immediately, but you will. When you are faced with a critical choice in life, I hope you will think of this book.

✵

What does it mean to have ‘wild problems’? The first thing you need to know is that the world’s puzzles are called puzzles because they often don’t have clear definitions and outcomes like those math problems you did in school.

Like the ‘tricky problems’[2] that we have talked about in our column before, they are problems that do not have a correct solution, an ending, or even a way to comment on the winner or loser. For example, the New Crown Epidemic is a tricky problem, no matter how you respond to it, the result is not going to be ideal, and no matter what you do, you are just barely maintaining the situation.

Wild problems, as Roberts puts it, are a different kind of problem. Wild problems may have a happy ending, but when you start facing them, you may not even understand the meaning of the question.

For example, most people in the world go with the flow, since everyone has kids, I want to have kids too. But some people will think more about it, saying that if they have children, their career will suffer and their quality of life will go down, and they will be very hesitant.

For these people, whether or not to have children is a wild question.

Please note that this is the time to test your thinking level. Let’s not talk about how to solve the problem, many times you can analyze a problematic situation clearly, and that’s already amazing. One of the great things about this book is the exercise of thinking skills.

Philosophers have a key perception about having children that people don’t think about [3]: you who don’t have children yet can’t assess the state and preferences of you who do.

It may be that you usually hate children, but when you actually have one yourself, you love that child more than anything else in the world. The old you can’t imagine that you are no longer the same person with a child.

Then a problem like having a child is one where you don’t get to use rational decision making. Rational decision-making requires that priorities be given, and priorities come from values, but how can you make decisions when you don’t know what your values will be when the time comes?

✵

Along these lines, Roberts divides life’s problems into two categories, ‘wild problems’ and ‘domesticated problems’, corresponding to wild and domesticated animals. Domesticated animals are predictable, and you very much know what’s going on with pigs, horses, cows, and sheep; wild problems, are unpredictable, and you don’t even understand what they are.

For example, if you have resolved to go to Shanghai to work and live, and you want to research how to get there, this is a domesticated problem. You can find all kinds of tips, ask people how to find a job, how to rent an apartment, etc.. Your goal is clear, and you can evaluate the efficiency of each step of action in an objective way.

The wild question, on the other hand, is whether to go to Shanghai. You don’t know what life in Shanghai is like. Is it easy to find a job? Is the salary enough when the house is so expensive? Will you be able to adapt to the climate and lifestyle in Shanghai? The goal in the wild question is subjective and difficult to measure.

There are various proven, scientific and rational approaches to the domestication problem.

The most basic approach is to weigh the pros and cons. You look at how many options you have, measure how much each option is worth, and then pick the one with the most value.

Or you can use the ‘moral algebra’[4] invented by Benjamin Franklin. Get a piece of paper and write down on the left side the reasons why you would do the thing, and on the right side the reasons why you would not do the thing, and let the equivalent reasons on each side cancel each other out, and see if the last remaining reason is to do it or not to do it.

A more scientific approach, as Daniel Kahneman has argued many times in his book Noise, is to find a formula to calculate the score [5]. Whether it’s recruiting or determining the health of a newborn, a simplest formula works better than a person’s subjective perception.

But for wild problems, these methods don’t work so well.

✵

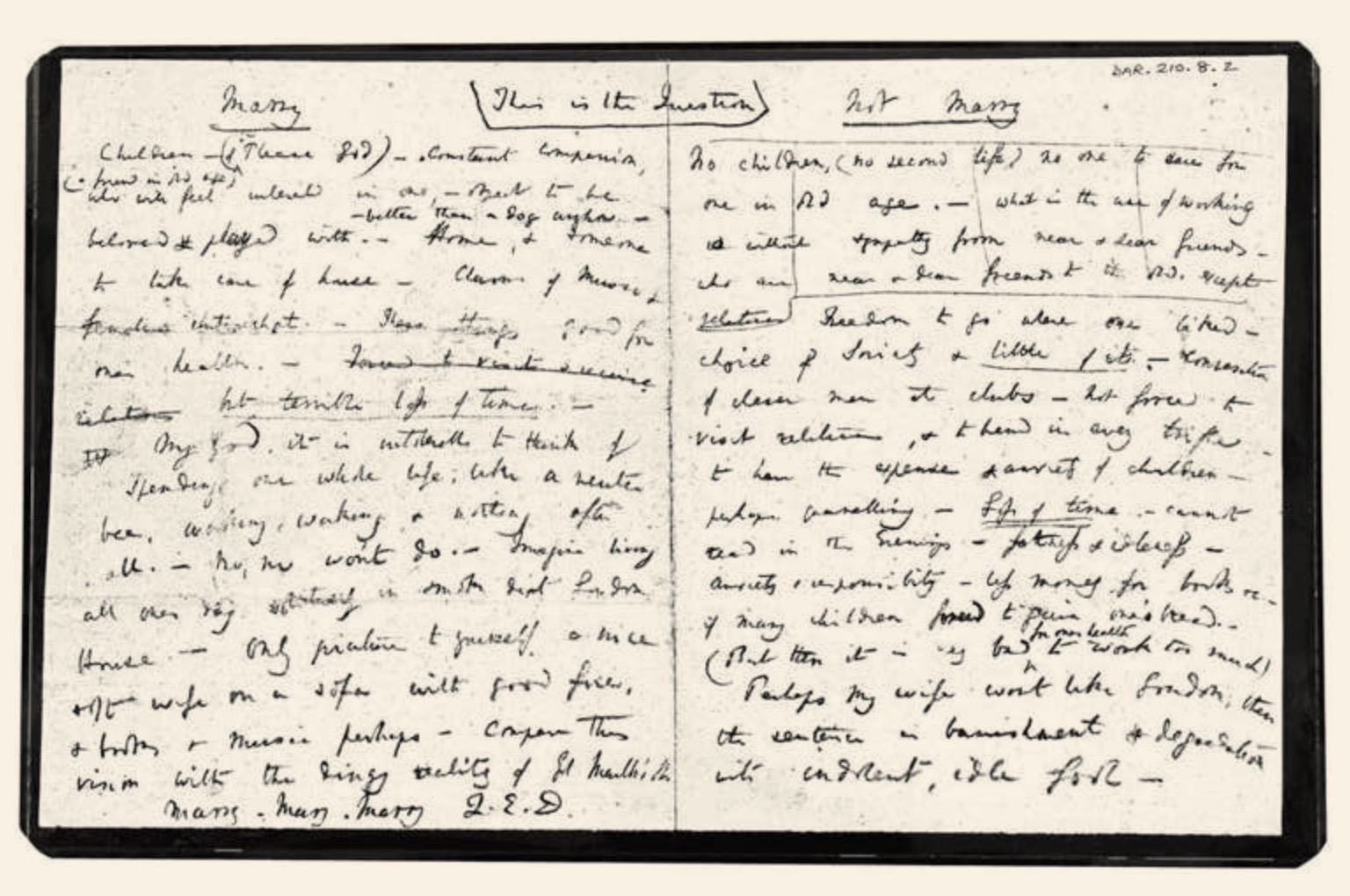

Perhaps you remember we’ve talked before about how Darwin once wrestled with whether he should get married [6]. He used Franklin’s moral arithmetic - writing on the left side of his notebook the reasons why he should get married, and on the right side the reasons why he shouldn’t.

Reasons for getting married include that he will get companionship, he will have women to gossip with, he will have children in the future to take care of him in his old age, he may be healthier if his wife supervises him to be less obsessed with his work, and he will have someone to take care of the house ……

Reasons not to get married include that he may have to leave London, he may lose his autonomy, he may have to waste time entertaining his wife’s relatives, having children will cost money and he will have to find a real job to support the family, and more importantly there will be no time to read in the evenings ……

Note that while Darwin listed various pros and cons, in the end he did not make his decision to marry based on the pros and cons analyzed in his notebook. He only found one reason - one can’t just work, he still wanted to be a family man. Because of this one reason, he discarded all the reasons and decided to get married!

Roberts revisits Darwin’s method of judgment and finds it highly problematic.

Darwin was missing a key cognition. Darwin did not understand what married life was really like! Darwin, as a single young man, had only met a few married people, and might have heard them occasionally talk about married life. But how much could he hear? There is a lot of privacy in real married life, so how would people tell you about it?

How can you make a good decision about marriage when you don’t even know what it’s like?

Roberts borrows a classic analogy and says it’s like a man who has lost his keys looking specifically for them under a streetlight. The key could be lost anywhere, and the reason you’re only looking under the streetlight is because you can only see under the streetlight. It is obviously wrong to assess something by the fact that you can only see it.

But that’s not the worst of it. The most serious trouble is that Darwin doesn’t know what kind of a person he will be when he gets married.

✵

A female philosopher named Laurie Ann Paul once offered an analogy. Assuming that ordinary people can become vampires, ask, would you like to become a vampire. If you become a vampire, you will have to suck other people’s blood for a living, sleep in a coffin every day, and not be able to see the sunlight. For you who are an ordinary person, of course you don’t want to live this kind of life, you think it’s too ridiculous. But then you go and interview the vampires and realize that the vampires have an extremely high opinion of their lives and are all very happy! They love being vampires, they love sucking blood, they love living in coffins, they don’t want to see the sunlight.

Would you like to be a vampire if the setup was that being a vampire would make your life enjoyable?

One of the weirdest things about this situation is that when you become a vampire, what you like and don’t like, changes.

That’s the crux of the wild problem. Choosing a major, getting married, having kids, moving to another city, all of these issues are really vampire issues. If you haven’t gone to Shanghai yet, you don’t know what you’ll be like in Shanghai and what different preferences you’ll have.

Then how else are you going to decide if you want to go to Shanghai or not? What’s the point of any moral math, algorithms, or formulas?

✵

Yet countless people get married and have children every year, including traveling to Shanghai. There are solutions to wild problems. How have we all solved it?

A Danish mathematician and poet named Piet Hein came up with a simple solution: flip a coin. Toss the coin in the air and see if it falls heads or tails to decide whether you go or not.

Note that this solution doesn’t mean that you should leave the decision-making to randomness. Hein’s insight is that flipping a coin makes you realize what you want the outcome to be. As the coin spins in the air, you mentally want it to land on a certain side.

By the same token, the act of making Darwin’s list of moral arithmetic really serves not to help him weigh the pros and cons, but to help him figure out what that thing is that he really desires.

You have actually decided in your intuition. What is that intuition? It’s obviously not something utilitarian, it’s not calculated.

*Roberts believes that that intuition is what you want your life to mean. It’s your purpose, your longing, your desire to participate in something bigger than yourself, your desire to go beyond your current life. *

✵

More accurately, Roberts again uses a word from ancient Greece that we’ve covered in previous columns: Eudaimonia, which is generally translated as “happiness” in Chinese, but more accurately means that you engage in an endeavor that brings out the best in you, so that it continues to grow and thrive. Roberts suggests that the word should be translated as “happiness”. Roberts suggests that the word should be translated as “Flourishing” - for an individual, flourishing means that you are living a prosperous life, that you are thriving.

You want to go to Shanghai because you think it will make you prosperous. Your quality of life won’t necessarily go up, you’ll be busier, you may be forced to live in a smaller room, you may not have enough money to spend - but the potential in you can be realized in Shanghai, your energy is higher.

Prosperity is about people living life to the fullest. Not just to be free from suffering, but to live with meaning, virtue, dignity, and autonomy, to exercise all the possibilities that are available to you. Just like a tree, you want to blossom and flourish.

When we watch the sci-fi show Star Trek, the Vulcans have a hand-raising salute - middle and index fingers together, ring and pinky fingers together, and thumbs spread as wide as possible - with a blessing: ‘Live long and prosper’, “ Live long and prosper,” which some Chinese netizens translate as “both longevity and eternal prosperity. You can’t just live long, you have to prosper as well.

Why do you have to get married and have children? Because you want to prosper. A family will make your life complete and your life prosperous, and for that you don’t care to sacrifice time and money.

To put it this way, we can roughly divide the world into three kinds of people -

**The first is a slave of desire.**He does whatever attracts him, driven by his own good and evil, and by outside coercion, lacking in thought and without overall planning.

**The second type is the refined egoist.**He is highly rational and wants to maximize his happiness in life. But he can’t give up on himself, won’t commit to a marvelous cause, and is always calculating.

**The third type is the prosperity seeker.**The purpose of his life is not to maximize happiness, but rather he wants to maximize all aspects of his potential, live a meaningful life, and preferably leave a mark. To this end, he is willing to sacrifice a certain amount of happiness.

It can also be said that everyone is a mixture of these three in some proportion.

Roberts’ book is about living this life as well as possible as a third person. It’s a small book, and its main function is to help us think through our problems. In fact, once you’ve got your problems straightened out, you’re already halfway there.

✵

This talk summarizes that, using the example of Darwin’s marriage, the wild problem is characterized by three things -

First, you don’t fully visualize the outcome of your choices; you don’t know what each option means;

Second, you don’t know what this choice will turn you into, and you don’t know how the changed you will evaluate that option;

Third, there are some pursuits that are more important than everyday happiness, call them prosperity.

How do you achieve prosperity? Let’s talk about that in the next lecture.

Annotation

[1] Elite Day Class, Season 1, Adam Smith in That Time and This Time (above) (below)

[2] Elite Daily Lessons, Season 3, Simple Problems, Dilemmas and “Tough” Problems

[3] We’ve talked about this before in our columns: Critique of Rationality in Decision-Making, You and Your Desires

[4] Elite Daily Lessons Season 1, What Exactly is Awesome Decision Making?

[5] Elite Day Class Season 4, Noise 5: Why Processes Are Better Than People

[6] Elite Day Class Season 1, Mathematicians Tell You Why It’s Hard to Be Confused

[7] Elite Day Class Season 3, Nine Work Lies 5: Life is not just work, work can be life

Get to the point

There are three characteristics of wild questions:

First, you don’t fully visualize the outcome of your choices; you don’t know what each option means;

Second, you don’t know what this choice will turn you into, and you don’t know how the changed you will evaluate that option;

Third, there are some pursuits that are more important than everyday happiness, call them prosperity.