Evolutionary Ideas 4: Guided Decisions

Evolutionary Ideas 4: Guided Decisions

Let’s move on to Sam Tatum’s Evolutionary Ideas. This book talks about using the heuristic of the human brain system1 to think fast and use a variety of flexible techniques to influence people’s decisions and behaviors.

To get people to do what you intend, traditionally it is usually coercion or enticement. If you force an order, people will resent it even if they obey; if you use economic incentives, it may cost you too much. Behavioral approach instead is to influence the person in a silent way, with some subtle designs that cost almost nothing - and he feels that he wants it that way.

You say there is such a thing as a good thing in the world? Yes, but the effect is not absolute, sometimes it doesn’t work - but it will surprise you with its effectiveness.

The subject of today’s talk is helping to make decisions without limiting choices.

✵

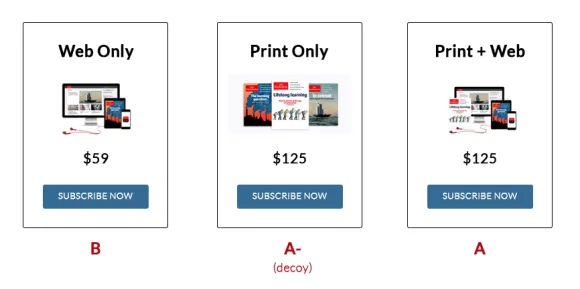

I’ll start with a particularly famous example, as told by MIT professor Dan Ariely in his book Weird Behavior. There was a time when The Economist magazine had three subscription options like the one below–

The first option was an online-only version for $59 per year; the second option was an online plus paper version for $125 per year – two options you might have to weigh up, the pros and cons of spending a little more to read the comfortable paper version and saving money by only reading the online version. What’s interesting is the third option.

The third option is paper only, no online version, and pricing is also $125 per year.

At first glance, this is an insult to the consumer’s intelligence. Because as I just said earlier, $125 allows you to subscribe to both the online version and the paper version, so who would choose to read only the paper version?

That’s where the trick is. The real role of the third option is ‘fake target (decoy)’, no one will choose it, but it serves to make the second option more attractive.

When there were only two options, A and B, you didn’t know which one to choose. Now there’s an extra third option, which is significantly worse than option A, and is the equivalent of an A-: then against it, A suddenly becomes more enticing. Between A and B, you would have had no good reason to choose either one, and perhaps you would have simply not chosen; now with A-, you have a reason to choose A.

It’s not a good reason, because it still doesn’t address how A and B compare - but “making a choice” isn’t a rational calculation in most cases. Now your System 1 finds option A attractive, so you choose A.

And A is exactly what the merchant wants you to choose. The results of the experiment bear this out. It’s called the “Decoy effect “. Sometimes a store will intentionally put an expensive and bad product on the shelves as a false target to set off the one next to the one it really wants to sell; sometimes a restaurant will intentionally have one or two obviously overpriced dishes on the menu, which is also a false target.

In his book, Tatum talks about how even animals eat this up. An experiment was done with Canadian jays. Raisins were placed in two locations, one raisin in the close location and two raisins in the far location. The jay showed laziness and mostly chose the closer location. But if you add an option for it to put two raisins at a greater distance as well, then the second option - which is to have two raisins at a less distant place - becomes more flavorful. The likelihood of a jay choosing the second option in the experiment did increase significantly.

We make decisions that are usually quick judgments dominated by System 1. System 2 is very lazy; it’s generally reluctant to step in and intervene, deferring to System 1’s decisions.

This technique has now evolved into a discipline called “Choice Architecture “, which specializes in how to influence your choices by designing the layout of options. There’s no bullying or baiting here, I do a little simple layout to guide you, and then you think it’s your decision.

- The environment in which the decision is made affects the choice of decision, and insignificant details can sway your behavior. *

We’re talking about three techniques: defaults, concretization, and chunking.

✵

The simplest bootstrapping is setting default values , which is the central idea of that book, Boost, by Nobel Prize-winning economist Richard Thaler.

For example, many people in the U.S. don’t really want to save for retirement, but if you set a default setting to save a certain percentage of your monthly paycheck for retirement when you fill out a form at orientation, that money is saved, because people are too lazy to change it. If you change the default option for lunch in the cafeteria menu to healthy recipes, people will eat healthier. If you issue a driver’s license with a default consent for organ donation, the consent rate reverses, etc., etc., etc. All of these defaults are the most flexible settings that you can reject and change with a move of your hand or mouth, but most people accept them.

There’s also a more subtle psychological element to the defaults, which is that they make you feel like it’s the socially sanctioned option, that everyone expects you to choose that way, and that you feel a little awkward if you don’t.

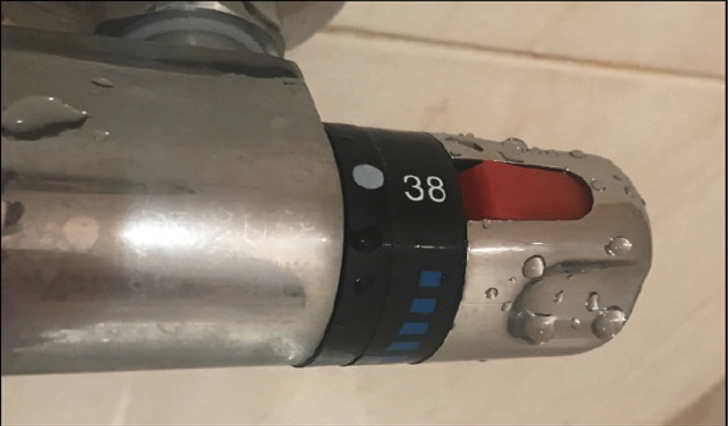

Hotel showers have a rotary switch that adjusts the water temperature, and if you mark it specifically 38 degrees, people assume that 38 degrees is the perfect shower temperature.

There’s a TV that comes with Netflix and Amazon play buttons on the remote, and you see both and assume that’s the video service everyone should subscribe to.

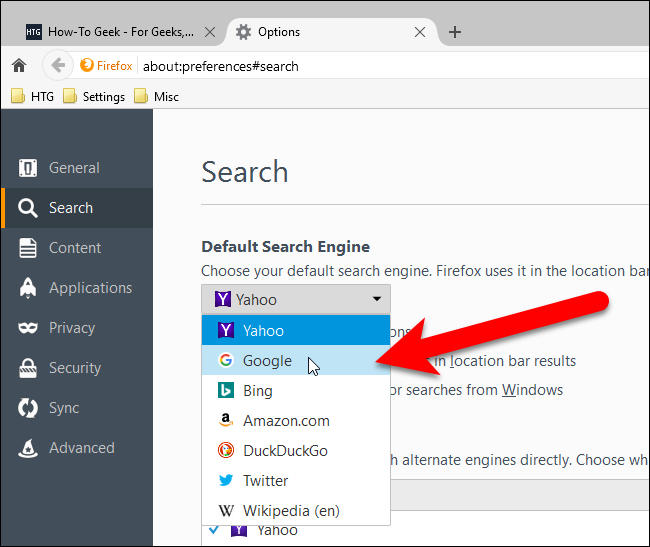

Then again, Firefox is a standalone browser, not attached to any operating system, users download and install it themselves, and it’s free. So what does Firefox make money on? Each browser has a default search engine, you enter what keywords, it automatically jumps to the default site to search. Of course, if you don’t like the default, you can change it, but the default is worth a lot of money.

Mozilla, Firefox’s parent company, generates over 90% of its revenue from this ‘default’ [1]. It has partnerships with several search engine companies, the biggest of which is Google. 2021 to 2023, just for making Google the default search engine, Mozilla will get $400-450 million in annual revenue.

Default is that powerful because default is the most convenient guide to human behavior.

Of course you can also use defaults for public good. For example, many children in India are not very hygienic, often don’t wash their hands properly, and get sick easily. There is a company that mixes soap powder into chalk, and when children write and draw with chalk, they get a handful of soap, so they can wash their hands again and get clean ……

The spirit is that you don’t need to be “convinced” to do anything, you are already doing it. For the “default” you, you don’t need a reason to do, you need a reason to not.

✵

But sometimes one has to be allowed to choose once, and you can’t say that anyone who doesn’t come out to vote on Election Day counts as voting for Hitler by default. Then we have another technique that’s slightly less powerful than the default, but also works well, and that’s to make an option appear more ‘prominent’.

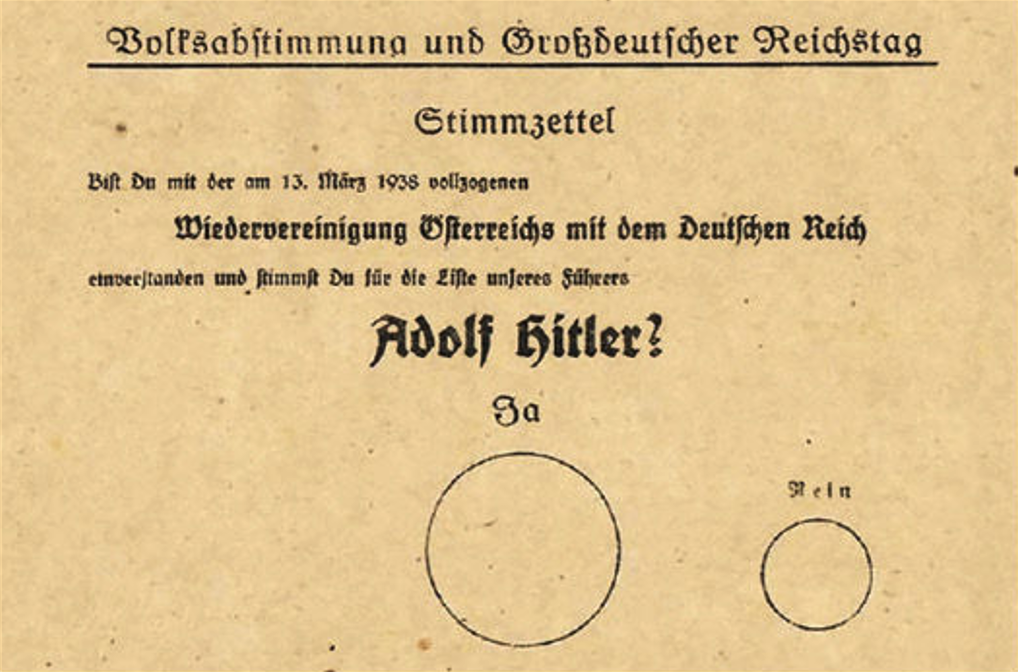

In 1938, Hitler’s Germany held a local referendum after annexing Austria: do you agree with Austria’s merger with Germany and support the list of names appointed by our leader Hitler? In this ballot, the circle of “yes” is much bigger than the circle of “no”.

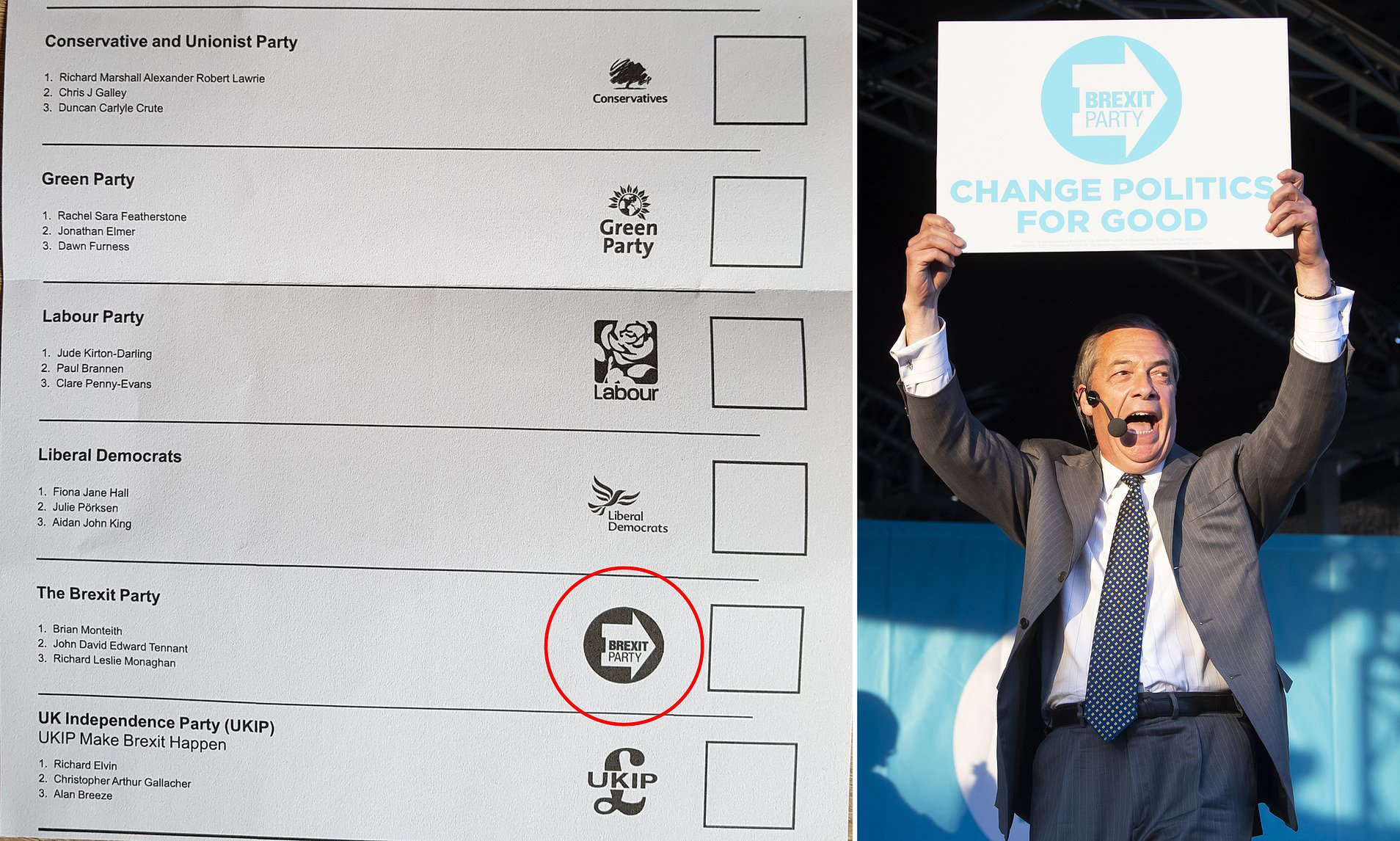

Then you say Hitler was unreasonable, surely modern people don’t do that - then you’re wrong. The one below is a ballot paper from an election in the UK in 2019–

The Leave Party’s logo design is a large arrow pointing to the right, and the ballot paper happens to be designed to tick a box on the right. To psychologists, this is blatantly suggestive.

The fact that many voters don’t understand or care about politics. So you’re saying that even if they don’t care, they don’t see the arrow and check the box? The reasoning lies in the fact that the human brain can process images far better than words. Evolution allows us to even process multiple images at once, yet we can only look at text character by character. Text is still very new to the brain compared to evolution.

That’s why graphing is a great way to make an option stand out. Graphics allow the brain to process information more smoothly, and smooth means fast, and fast means it’s more likely to be picked.

You go to a restaurant and order food, and many of the dishes on the menu are in plain text, but there are a couple of main dishes displayed graphically, so you can imagine that you’re more likely to pick the main dish.

Some Japanese restaurants use wax and plastic materials to make high-fidelity models (called sampuru) of various dishes, which are displayed directly for you to see, so what you see is what you get. You know exactly what you want to order as soon as you look at it, so you accelerate your decision to eat there.

Another example where a picture is worth a thousand words is the “Beware of slippery floors” sign that is placed on freshly mopped floors in public places. Experiments have shown that the most effective sign design is to make it look like a banana peel: because everyone in the world has seen the cartoon about stepping on a banana peel and falling down ……

✵

Our third technique is to ‘chunk’ the information, i.e., to package it so that there are fewer options.

Tatum is probably quite familiar with China. He says that if you were asked to buy five spices - cinnamon, fennel, star anise, peppercorns and cloves - you could get them, but you’d find it so much of a hassle that you wouldn’t bother to buy them at all - whereas in China, they’re packaged up as ‘five spice powder’, and you can just buy this one seasoning - how convenient is that?

Also, when you order at McDonald’s, you can actually order everything separately, but McDonald’s offers the option of a ‘set menu’, so ordering is very easy.

That’s why even telecom services are now packaged. Another example is traveling, of course you can make your own daily itinerary, but that’s a big hassle; travel agencies make a “Hangzhou three-day tour”, “Yunnan luxury four-day tour”, each package has a price, and you can look at it if you are willing to study it, or just choose one based on the name. According to the name to choose a good, save effort.

This talk is about making it easier for you to accept the decisions I want you to accept by shaping your choice environment.

The human brain is really reluctant to make choices. Faced with a dense pile of options, some of which may be high quality and high price, some of which are cheap and you’re worried about the quality, and some of which seem to make quite a bit of sense and you’re not sure if they’re right for you …… you’re really reluctant to compare them carefully one by one and you want to turn around and walk away.

*So the underlying idea that guides choice decisions is to make it either unnecessary to make choices, easier to make choices, or fewer choices. *

For the consumer this convenience comes at a price. You shop online, and the default option may be to automatically subscribe; you sign up for a social platform account, and the default option is to allow it to collect information about you; you buy a smart TV, and it’s already loaded with a bunch of apps you don’t even need.

Tatum also expressed concern that the reduced options could be misleading. If you take your blood pressure, for example, and you’re given a specific number, you might not understand what it means; if there are options for high, normal, and low blood pressure, you can be reassured when you see that your result is “normal”. But aren’t there different kinds of “normal”? If the system can categorize normal into “normal but low” and “normal but high”, people will know more about their health.

In a sense, ‘choice architecture’ makes people stupid. The first thing an expert should do when he gets a new computer is to change the browser, change the search engine, customize his options, and uninstall the software he doesn’t use.

Of course often it doesn’t matter, you just want to go to a Japanese restaurant to eat a bowl of noodles, you willingly accept the arrangement of the merchant. But we must understand: * ‘Customization’ is the manipulation of people. “Being ‘customized’ should make you feel a little uncomfortable. *

If you’re a merchant, you can customize defaults for others; if you’re a consumer, you can use customization to fight defaults.

Annotation

[1] https://www.pcmag.com/news/mozilla-signs-lucrative-3-year-google-search-deal-for-firefox

Highlights

- make it easier for you to accept the decision I want you to accept by shaping your choice environment.

- guide decisions with a three-pronged technique: defaults, concretization, and chunking.

- the underlying idea of guided choice decisions is to make it either unnecessary to make a choice, easier to make a choice, or less of a choice.