Don't Trust Your Gut 5: Ability x Luck

Don’t Trust Your Instincts 5: Ability x Luck

In the last lecture we said that effort and luck should be multiplied, and this lecture is about the multiplicative relationship between ability and luck.

“Effort” is when you spend time and go for quantity. If you put in 30 resumes when others put in 15 resumes, you are working hard. “Ability” is about quality, the gold content of your resume.

Effort in many cases is the “r strategy”, casting a wide net, it does not matter how many times you fail, it is good to seize an opportunity; ability is the “K strategy”, there are only a few important opportunities, you not only have to seize every opportunity, but also to use it to the extreme, to develop and grow.

For things like dating and finding a job, effort is important; for big things like making a company bigger and stronger, ability is more important.

In his book, Seth talks about the history of Airbnb’s growth, which I think is particularly telling. This talk will also give you a better understanding of the Silicon Valley startup scene.

✵

Airbnb’s “beginnings” don’t sound like much of a stretch. Once upon a time, two young men, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, alumni from art school, rented an apartment together in San Francisco.

In October 2007, there was a big rally in San Francisco and the local hotels were fully booked. The two men, who were unemployed and short of money at the time, thought that they could squeeze a few more people into the apartment they were renting. It seemed like a service, too, and the two could offer air beds and breakfast to their residents. The ad went out and people actually came to rent it.

Things had been pretty unusual so far, and there’s no telling how many young people in the world have done similar things. But next, unemployed youths Chesky and Gebbia, made a less unusual decision. They wanted to turn the whole “temporary lodging” thing into a business, and instead of offering lodging to people themselves, they set up a website where anyone with a spare room could offer it.

The two happened to have a mutual friend named Nathan Blecharczyk, a computer whiz, who helped set up the site.

The site’s name was long at the time, airbedandbreakfast.com, which means “air bed and breakfast”.

Note that the business model at this time was that you come to my house, I’m home at the same time, so we squeeze in, and I provide you with breakfast. That’s a different model than Airbnb’s current model.

The website is up, but there’s no business. There are not always large gatherings, and people are used to staying in hostels after all. After a period of time without much income, Chesky and Gebbia credit card debt accumulated 20,000 U.S. dollars, the programmer Blake Chick saw no future and went to Boston to look for work.

Chesky and Gebbia still do not die, they specialize in large gatherings to promote the business. Austin, Texas, has an annual gathering called South by Southwest (SXSW), which attracts artists, geeks, and innovators from all over the world, so the two went there. The business turned out to still not be great, but they met a Silicon Valley guy at SXSW named Michael Seibel.

Seibel was extremely well-connected in Silicon Valley and seemed interested in Chesky and Gebbia’s business.

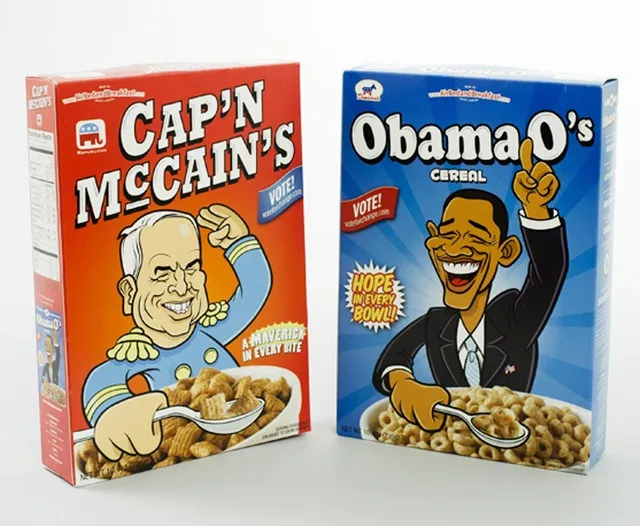

The next big rally is the 2008 Democratic Convention in Denver. Chesky and Gebbia kill it again in Denver, the business still isn’t working, but the two have gotten a new business going. They packaged a breakfast cereal with Obama and McCain on the cover and sold it on the floor, and it sold well, just in time to pay off their previous debt. Unfortunately, this kind of dabbling business is unsustainable.

At this time, Seibel introduced a Silicon Valley venture capital company called Y Combinator, referred to as YC – this company is still very famous.YC CEO at that time is Paul Graham (Paul Graham), this person is the author of the geek masterpiece “Hackers and Painters”, Silicon Valley, big brother level characters. This person is the author of the geek book “Hackers and Painters”, a Silicon Valley bigwig, and his status in the jungle is much higher than that of Li Kaifu in China.

Graham wasn’t a big fan of Chesky and Gebbia’s business model, but when he heard they were selling cereal at the Democratic convention, he thought the spirit was commendable and gave $20,000 in seed money. So they recruited programmer Blackchick back and the team survived for a few more months.

It was at this point that Airbnb had its epiphany moment.

A band drummer was going out on tour, had no one living in his house, and wanted to give Airbnb his entire house to rent out. Chesky and Gebbia originally thought this didn’t fit the company’s business model, as they envisioned the owner of the house staying at home with the guests, which would allow them to offer breakfast to the guests - but the drummer’s need was a real inspiration, and maybe people preferred empty rooms where the owner wasn’t home?

And so it turned out. So Chesky and Gebbia changed their business model to short-term rentals of temporarily unoccupied homes, and their website name became the more memorable airbnb.com …… Their business finally took off.

Then it was just a matter of time before Graham’s good friend Greg McAdoo, a partner at Sequoia Capital, recognized airbnb and provided a massive amount of startup capital …… The rest is history.

There’s a little more to this story.In 2014, Graham ceased to be the CEO of YC, and YC welcomed a new CEO, and who was he? He was Sam Altman, now the CEO of OpenAI. So you see, interesting things always happen in Silicon Valley because they have a circle.

As soon as Altman took office, he went to Stanford to give a class on entrepreneurship and came up with a formula for success:

Entrepreneurial Success = Idea x Product x Execution x Team x Luck

where “luck” is a random number between 0 and 10,000. The most important variable in this formula is obviously luck.

Examining Airbnb’s startup story, luck did play a big role: they met the origins of a large gathering, had a bigwig from the Silicon Valley startup scene to give investment, and got the inspiration to change the business model. And Chesky and Gebbia also worked very hard; they used to go wherever there was a large gathering to promote their business, which can be described as indefatigable.

But hard work and luck aren’t enough to explain their success. You also need competence.

✵

There is a way to systematically analyze the relationship between ability and luck. Some researchers have looked specifically at companies that have outperformed their peers on the stock market by a factor of 10, forming the ‘10X Club’. Companies like Amgen in biopharmaceuticals, Intel in chips, and Progressive Insurance in insurance have all outperformed their peers by a factor of 10 or more over a period of at least 20 years. How did they do it?

Of course you need a lot of luck. Take Amgen, for example. It was by chance that a genius scientist from Taiwan named Lin Fu-kun discovered a protein that helps the kidneys produce red blood cells, which allowed Amgen to develop a drug called Epogen - one of the most profitable drugs in the history of biotechnology.

Without such luck, Amgen could not be what it is today.

In order to systematically examine the importance of luck for these 10X companies, the researchers had to count the “good luck events” they experienced one by one. There are three criteria that must be met for a ‘good luck event’ -

the event occurs largely independently of the company’s actions: it is not something you create on your own initiative;

the event had a significant impact on the development of the company;

there are unpredictable elements in the event.

Based on these three criteria, the researchers found that each 10X company had encountered an average of seven good luck events.

In that case, luck is so important that greatness requires luck. But don’t worry, the researchers didn’t just count the good luck events of the 10X companies, they also counted the average, mediocre “1X companies” in their peer group.

For example, there was a pharmaceutical company called Genentech, which is a counterpart to Amgen, and the researchers found that it too had experienced some key good luck events. For example, it was the first to enter a lucrative market by making artificial insulin just a little bit ahead of everyone else.

So why haven’t companies like Genentech reached 10X size? Is it because they have so few good luck events? Not really.

Researchers have found that there is no statistically significant difference in good luck events between 10X and 1X companies. In fact, 10X companies encountered an average of 7 good luck events, but 1X companies encountered an average of 8 good luck events!

This means that the average company has just as many, or perhaps even more, opportunities for good luck, they just don’t take them, or they don’t take them as well, and they don’t use them as well as the 10X companies, who are strong because they maximize the benefits of their good luck.

There is a competence issue here.

Let’s look at Airbnb. Yes, it’s lucky, but the two founders are also very capable. Chesky and Gebbia actively reached out to Silicon Valley bigwigs, networked, applied for YC support, and moved on to a new idea as soon as they realized their original idea wasn’t as good as the new one…is this something that young people can usually do?

During the New Crown Pandemic, Airbnb saw a 72% drop in business, resulting in the company quickly cutting costs and shifting to a greater focus on long-term stays. They generously gave refunds to guests, gave very generous severance packages when they fired employees, and accumulated a great reputation that furthered the brand …… As a result, profits in 2020 performed so well that the IPO valuation was surprisingly over $100 billion.

**These high level decisions are competence. * Competence *Competence can turn into good luck when it meets bad luck. *

✵

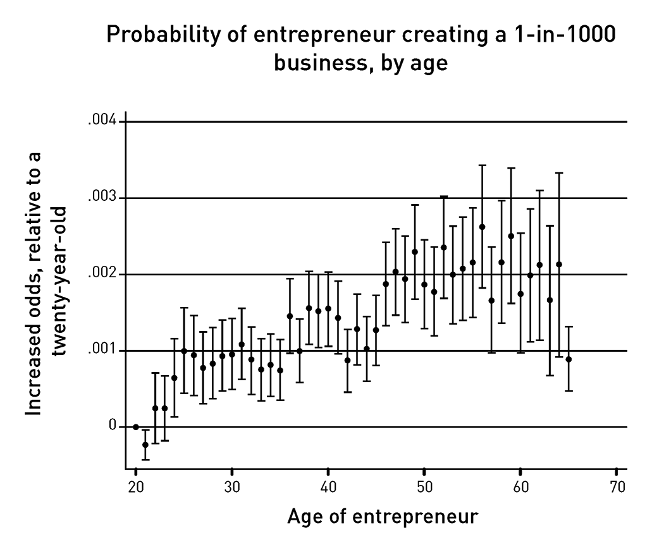

We can also analyze the relationship between ability and luck from another angle. The Silicon Valley myth of a few young people with neither unique skills nor much accumulated experience starting a business and making a fortune because of a good idea, like Airbnb, is not really typical. The more common entrepreneurial successes are actually middle-aged people.

Someone surveyed 2.7 million entrepreneurs and found that the average age of U.S. business founders is 41.9 years old. And as long as it’s before the age of 60, the later they start their business, the more likely they are to be successful in their venture–

So do you think it’s because there are a lot of traditional industries here, and high-tech industries should be for young people? Neither. The average age of founders in the high-tech industry is even greater, at 42.3 years old.

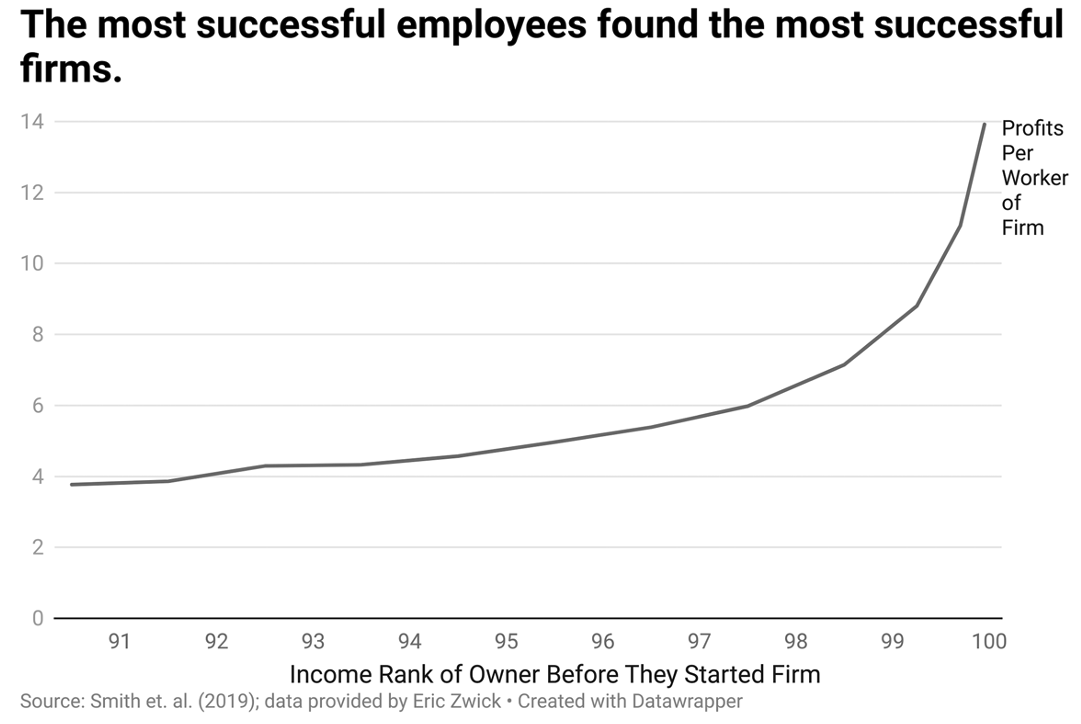

What is common is that successful entrepreneurs are not the kind of young amateurs who are new to the field, but middle-aged insiders. These people have usually been working in the relevant field for a long time. Statistics show that people with experience working in the relevant field are twice as likely to succeed in their business as those with no experience. The following chart is particularly illustrative -

- The more you earned while working in the field before you started your business, the more profitable that company of yours will be after you start it. *

The reason why there was opportunity for amateurs in that Airbnb story was because it was a brand new field. For mature fields, it’s often best for the best people in the field to come out and start a business.

A prime example is Tony Fadell, the founder of Nest Labs. This man started his business in his mid-forties and his main product was a home thermostat.

Prior to starting his own business, Fadell worked as an engineering director at Philips, where he learned about managing teams and financing; he also served as a senior vice president at Apple, where he learned how to improve the user experience. That said, before founding Nest Labs, Fadell had the best-looking resume in Silicon Valley. He made a lot of mistakes and learned a lot of lessons when he was much younger, and he’s built up a strong capability.

Seth says Fadell’s route represents a more universal formula for entrepreneurship – the

you spend years building up expertise and a network of relationships;

you prove you’ve been successful in the field;

you reach middle age and seize the opportunity to go out on your own and start your own company.

✵

Simply put, opportunity does love a prepared mind, and middle-aged people do have what it takes.

*Talent is also essentially a form of luck, but ability can be accumulated. Competence is the knowledge you’ve learned in the business, the experience you’ve had doing it, the partners you’ve worked with, the accomplishments you’ve made, and the mistakes you’ve made. Competence can be represented to a large extent by what you earn. *

- The same opportunity is in front of different people, and those who are more capable are better able to use it. *

The dogma of the older generation overemphasizes ability; the stories of the newer generation overemphasize luck. A more accurate understanding is ability x luck.

Get to the point

Competence is what you’ve learned in the business, the experience you’ve had doing it, the partners you’ve worked with, the results you’ve achieved, the mistakes you’ve made. Competence can largely be represented by what you earn.

The same opportunity is in front of different people, and those who are more capable are better able to use it.